How Three Dunfermline-Born People Quietly Changed the World of Ballet

It is a remarkable fact that Dunfermline can claim not just one, but three former pupils whose work changed ballet across the world: Moira Shearer lit up the screen, Kenneth MacMillan reinvented narrative ballet, and Robin Anderson helped build Scottish Ballet into an international force. Together, they show how one Fife town quietly helped shape what ballet looks like, how it is run, and how millions experience it.

From The Public Park to Covent Garden

Moira Shearer was born Moira Shearer King at Morton Lodge next to The Public Park, Dunfermline, on 17 January 1926, and later attended Dunfermline High School before her family moved and she continued her education near Glasgow.

Early years in what was then Northern Rhodesia brought her first serious ballet lessons, but it was a move to London and a place at the Sadler’s Wells school at 14 that launched her towards the front rank of British ballet.

By her late teens, she was dancing leading roles with the Sadler’s Wells company, making a mark in works such as “The Sleeping Beauty”, “Swan Lake”, “Coppélia” and Ashton’s “Symphonic Variations”.

Her poise, musicality and distinctive red hair made her a natural star at Covent Garden, but it was cinema that turned her into a global icon.

The Red Shoes and beyond

Shearer’s performance as Victoria Page in Powell and Pressburger’s “The Red Shoes” (1948) became one of the most influential screen portrayals of a ballerina, introducing ballet to vast new audiences and inspiring countless future dancers.

The film’s blend of melodrama and dance made a Dunfermline‑born ballerina the public image of ballet for post‑war cinema‑goers around the world.

She followed with roles in “The Tales of Hoffmann” and other stage and screen work, while also writing and broadcasting about dance, helping to explain ballet in accessible language to non‑specialist audiences.

In doing so, she broadened ballet’s reach far beyond the opera house, proving that a classical dancer could straddle high art and popular culture without sacrificing artistic seriousness.

Kenneth MacMillan: Dunfermline’s radical storyteller

Kenneth MacMillan was born in Dunfermline, Fife, on 11 December 1929, the youngest of four surviving children of William and Edith MacMillan, before the family later moved to Great Yarmouth in search of work.

His childhood was marked by poverty and the early death of his mother, experiences that fed into the psychological darkness and emotional intensity of many of his later ballets.

Evacuated during the Second World War, he discovered ballet as a teenager in Retford; already a keen tap‑dancer, he switched focus and, aged 15, secured a scholarship to Sadler’s Wells Ballet School after audaciously forging a letter from his father to request an audition.

Stage fright curtailed his performing career, pushing him decisively towards choreography, where he quickly emerged as one of the leading creative voices of his generation.

Choreographer who changed the rules

MacMillan’s breakthrough works in the 1950s and 60s, including “The Invitation”, “The Rite of Spring”, “Song of the Earth”, and his hugely popular “Romeo and Juliet”, reshaped narrative ballet by tackling adult themes and giving dancers dramatically complex characters to inhabit.

He challenged genteel notions of ballet by staging scenes of sexual violence, political repression and psychological trauma, insisting that classical technique could carry the weight of modern drama.

As Director of The Royal Ballet in the 1970s, he both created major three‑act works such as “Manon” and “Mayerling” and broadened the repertory by inviting choreographers like Balanchine, Robbins and Tetley, permanently expanding what British ballet audiences expected to see.

His ballets remain central to repertoires worldwide, meaning that a choreographer born in Dunfermline continues to shape how companies from London to Paris tell stories in dance.

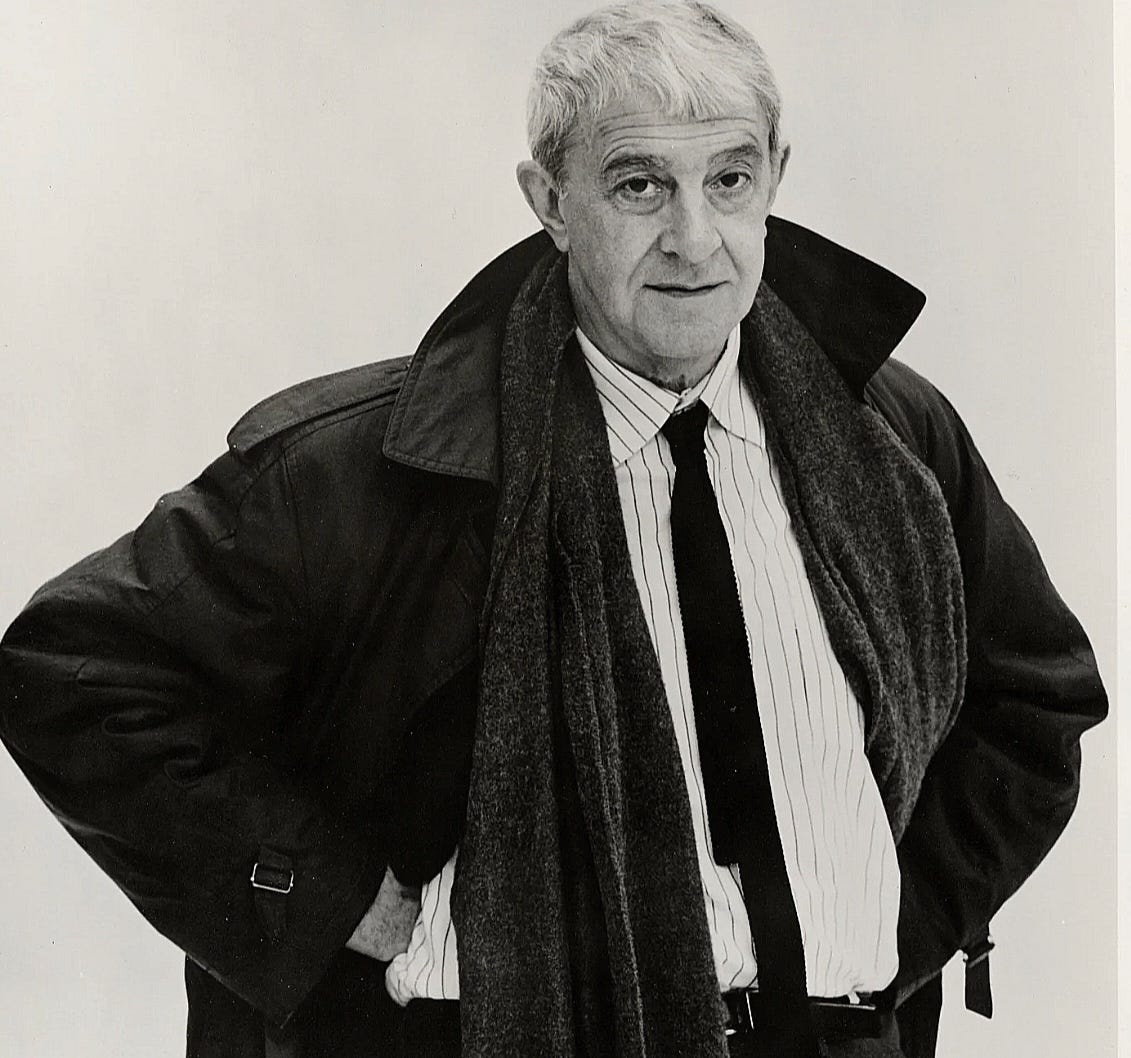

Robin Anderson: building a Scottish national company

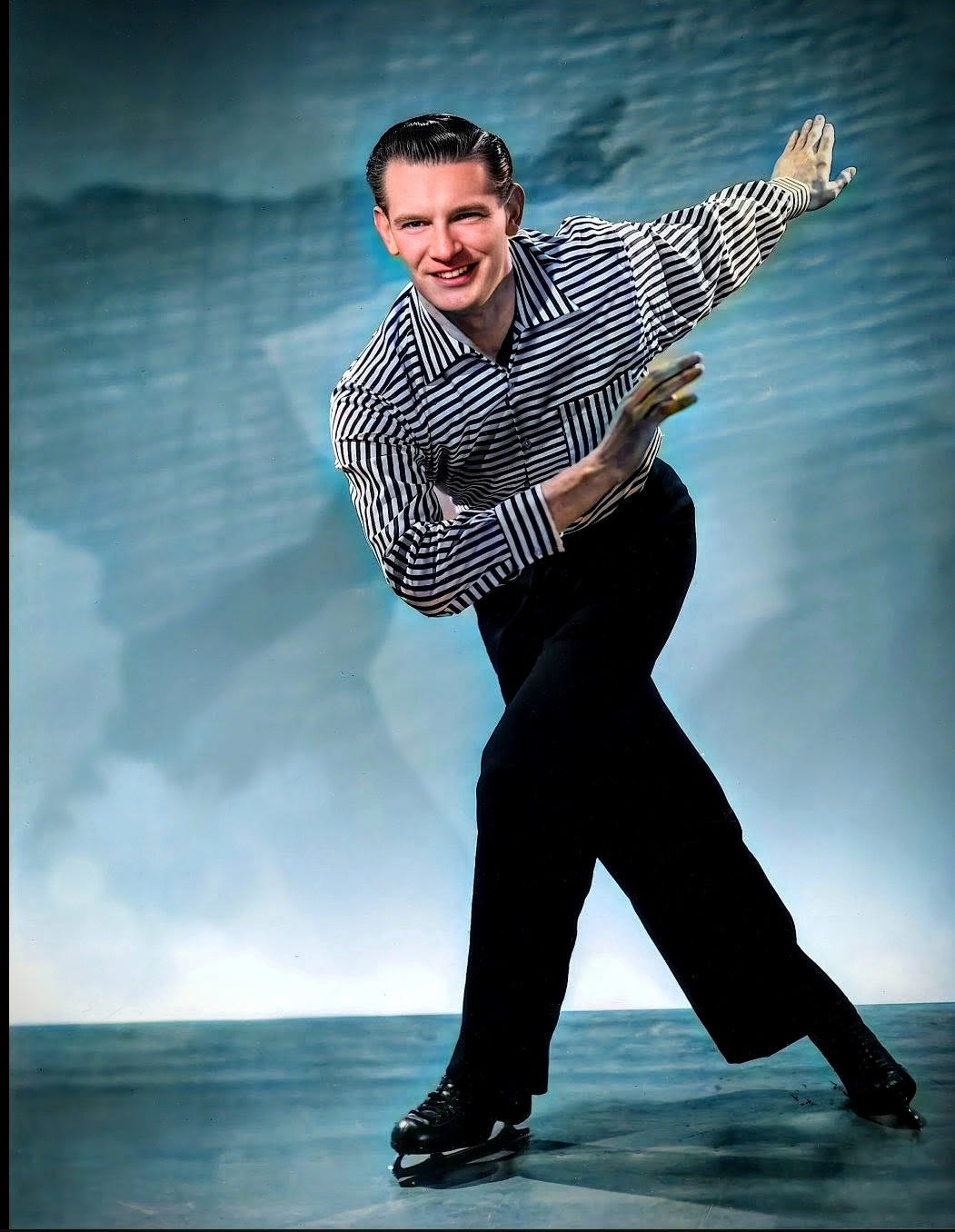

Robin Anderson was born in Dunfermline in 1931 and attended Canmore Primary and Dunfermline High School before a serious childhood cycling accident led to ice‑skating as physiotherapy.

He became Scottish figure‑skating champion while training as a pharmacist, but earlier injuries ultimately blocked a full‑time performing career and he spent years working in pharmacy in London and Edinburgh.

A change of direction came via an Arts Council bursary and a move into arts management, leading to his appointment as Administrator, and later General Administrator, of Scottish Theatre Ballet, soon renamed Scottish Ballet, in the early 1970s.

Working alongside artistic director Peter Darrell, Anderson’s brief was to integrate the company into the artistic life of Scotland and to establish it as an internationally recognised ballet company rather than a regional troupe.

Putting Scottish Ballet on the map

Anderson helped shape the company’s touring, repertoire and partnerships, inviting guest choreographers and expanding classic works so that Scottish audiences could see world‑class ballet at home while international audiences learned to associate Scotland with serious dance.

Under his watch, Scottish Ballet undertook ambitious foreign tours and collaborations that raised its profile and gave Scottish dancers experience on major stages abroad.

Colleagues remembered Anderson as a shrewd, demanding yet supportive administrator who paid attention to detail and understood that strong infrastructure and advocacy were as vital to ballet’s future as virtuoso pirouettes.

His role shows how someone from Dunfermline can profoundly influence ballet’s ecology without ever being in the spotlight, ensuring that companies survive, tour, and grow.

One town, three kinds of influence

For a town better known for kings, linen and football, the fact that three former Dunfermline residents ,born just 5 years apart went on to redefine ballet’s image, its storytelling and its institutional strength is quite frankly astonishing. It means that whenever audiences weep over MacMillan’s “Romeo and Juliet”, discover ballet through “The Red Shoes”, or watch Scottish Ballet on tour, a little of that experience can be traced back to a relatively small town in West Fife from one generation.

Thanks again for taking the time to read this article. If you have any suggestions or ideas you’d like us to cover, please just get in touch.

What a fascinating exploration of Dunfermline's unexpected ballet legacy. The contrast between these three figures is striking - Shearer bringing ballet to mass audiences through cinema, MacMillan revolutionizing choreographic storytelling with psychological depth, and Anderson building the institutional foundation that allowed Scottish Ballet to thrive internationally. It's remarkable that all three were born within just five years of each other in the same town. MacMillan's journey from forging his father's signature for an audition to becoming Director of The Royal Ballet is particularly compelling - adversity channeled into artistic innovation.

Thank you for your comment. It never ceases to amaze me when I find out stuff like this.